Killing Uniqueness: Goodbye, Kosher Halal Co-op

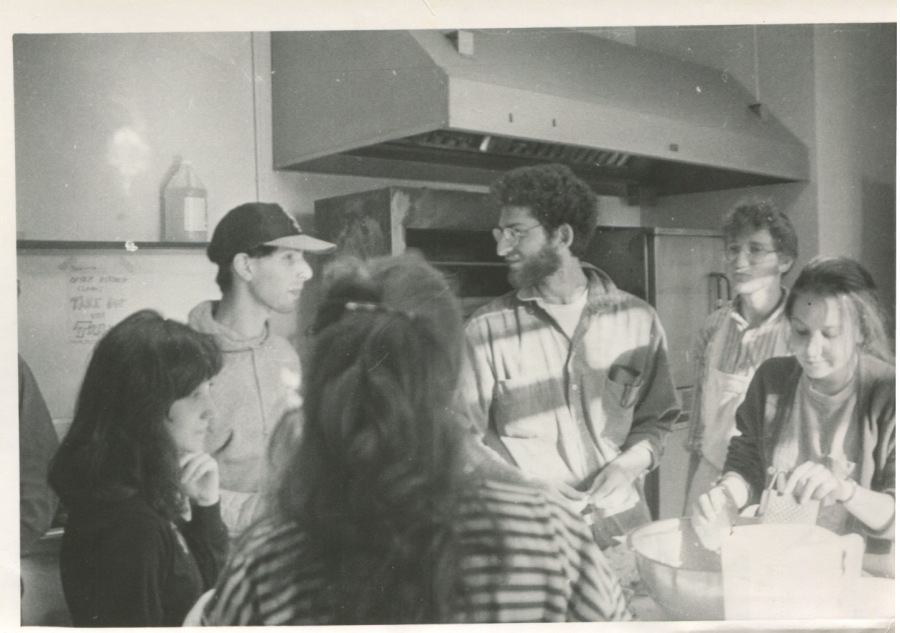

Kosher Halal Co-Op, 1990.

In One Oberlin’s path toward growth and profitability, the current administration possibly feels that all that is small, irregular, quirky, and unprofitable is a barrier to “modernity.” As I have expressed many times, in person and in writing, to the administrations of S. Fred Starr (as student and class president), Nancy Dye (as class trustee), and Marvin Krislov (as an alumnus), if a process of halcyon “modernization” keeps shearing away from Oberlin all that is strange and unique, you will be left with an expensive four-year college offering the same experience as many other campuses. This will play out in a post-pandemic world where American and global students, for at least the next decade, will ask really tough questions about what their college experience prepared them for in a world in flux — where the center of gravity in culture, economy, and innovation is shifting away from the United States.

A mania for lean operations, cost savings, scaling up, and profitability means a race to erase Oberlin from itself. The cookie-cutter receptacle that will be left in the aftermath will be a humdrum college that neither excels nor fails. There has been a steady stream of news from Oberlin that has stunned alumni — union-busting is anathema to the spirit of the Oberlin that led the way in the fight for labor rights. The latest is the news of the closure of Kosher Halal Co-op; Emi Ostrom also wrote about her concerns on Feb. 12. There have been signals that the administration considers student-run initiatives such as ExCo and OSCA to be fundamentally amateurish and unprofitable. After all, how could undergraduates be expected to manage courses, dining, and community? The preference is to infantilize current students as not knowing how to do things on their own.

Growing up in Bangladesh in the global backdrop of the United States’ low-level proxy wars against Iran, Libya, and other “disobedient” nation-states, we had expected a hostile environment for Muslims, at a granular level, in America. At the briefing for newly admitted Bangladeshi students held at the United States Information Service library in Dhaka, one student asked if he could bring his typewriter (it was 1989!) and another about his jainamaj (prayer rug). In that environment of distance and fear, Oberlin stood out to me not only as the rare school offering full scholarships to international students — we were still called “foreign students” back then — but also for three highlights of the catalog: ultimate Frisbee, Experimental College (I taught the Bangla language as an ExCo by my second year), and Kosher Co-op which “also offered halal food for Muslim students.” Most American college catalogs at that time were anodyne in their conformity; they offered the same dormitory, food, courseload, and campus grounds experience. Oberlin was remarkable for its commitment to making space for everything that would not find a home elsewhere.

From the first week on campus, Kosher Co-op exerted a gravitational pull on members far stronger than dormitory, classroom, or playing field. A co-op’s basic function is shared cooking, eating, cleaning, and maintenance — through it all, Kosher members talked, debated, and shared. It was the home of the Yiddish schmooze and the Bangla adda. Muslim-Jewish relationships, similarities and differences between Arabic and Hebrew, the possible futures of Palestine and Israel (the intifadah deepened these discussions), the slow disappearance of Yiddish dialect in the New World — all this we debated.

We did not agree on many things, but we disagreed in a spirited manner that proposed that the best education included these civil debates with our fellow students. We Muslim students learned fleischig, milchig, treif, and how not to let these three rivers meet. We wondered out loud why shrimp was somehow Halal for us but not Kosher for you. One pre-Shabbat, we discussed late into the night how to maintain Kosher-Halal by forsaking the wine marinade on a chicken dish. The thesis (the wine evaporates when cooking) and antithesis (that’s not the point, it’s the spirit of the process) came from a Muslim and a Jewish student, in that order. These spirited debates over food inspired the design of our annual t-shirt: a dialogue between Bert and Ernie over the finer points of treif.

I was forever making the error of carrying my backpack into the co-op on the weekend, breaking the Shabbat no-labor rule that kept our lights on over the weekend. Years later when I first encountered the phenomenon of the “Shabbos Goy” in the Williamsburg part of my adopted home of New York, I realized we could have been placed in that role at KHC but were not because we were never considered outsiders. When Hebrew Language Table was initiated at Oberlin in 1989, some Jewish students wondered if it was somehow alienating to the Muslim students and our reply was, “It’s once a week and it’s one table — it’s not really a big deal. It is not alienating to anyone.” It was always a gentle inclusion, so different from the bitter spirit of much of the world today.

In some direct, some indirect, and some unmeasurable ways, conversations at the co-op led to my first public op-ed for the Review (“A Muslim Speaks on the Rushdie case,” Feb. 9, 1990), a group letter opposing the new neocons such as Dinesh D’Souza (Feb. 22, 1991), a later essay on the campus debate over Edward Said’s visit, spirited conversations around campus events led by Students for Free Palestine, and the founding of the Muslim Student Group (whose faculty cosponsors were the Co-op’s Rabbi Shimon Brand and the college’s Islam Professor James Morris). After 9/11, when this country was gripped by security panic and the war of error, our first instinct as artist-academics in New York was to form Visible Collective to fight against racial profiling. The lessons of debate and organizing at KHC and the broader Oberlin campus carried us through that new fear-mongering environment with conviction.

The last time I visited Oberlin was three years ago for the alumni award event honoring Kamal Quadir, OC ’96. I made two side-trips — one to Professor Ron Dicenzo (who has since passed away) and the other to KHC to have Shabbat dinner with Rabbi Shimon Brand. During that visit, Brand introduced me to the Muslim Imam who was also now affiliated with KHC. I marveled at the change. In 1989 it would be hard to find an Imam anywhere in Lorain County, and the school had only one Islam-related class taught by Professor James Morris.

In its role in supporting the antebellum Underground Railroad, admitting African-American women, creating co-ed dormitories, working tirelessly in the fight against Apartheid, founding Third World House (Price dormitory), and beginning to decolonize its curriculum, Oberlin has innovated outside the classroom just as much as inside. If you keep neglecting inventive, genre-breaking, off-beat parts of Oberlin — OSCA, KHC, ExCo — you will be left with a milquetoast husk, a college experience identical to every other genetically smooth four-year offering. An inclusive co-op experience that brings Muslim and Jewish students together is a good place to start the journey back to the original Oberlin.

Naeem Mohaiemen, Class President ’93, Class Trustee ’94-’96, is a filmmaker and academic. He was a finalist for the Turner Prize and is currently a Mellon Fellow at Columbia University in New York.