Man, Animal or Albatross?

April 13, 2012

The idiom “a picture is worth a thousand words” refers to the idea that a complex concept is more easily represented by a single image than any number of words. First coined by Frederick R. Barnard in an article published in the advertising trade journal Printers’ Ink in the early 20th century, the phrase was originally intended as a commendation of the effectiveness of graphics in advertising. Last Friday night, College seniors Alexander Voight and Jillian Kron proved the truth of Barnard’s statement, translating literature into visual data to construct the content of their Senior Studio shows.

The title of Voight’s show, Albatross, makes direct reference to Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s poem “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner.” In the poem, the albatross stands as a metaphor for a psychological burden, so powerful that it feels like a curse. The narrative premise is based on an albatross that begins following a ship at sea and subsequently gets shot by a suspicious mariner with a crossbow who blames the bird for the dangerous weather. As punishment, however, both the mariner and his ship are cursed, and he is forced to wear the dead albatross around his neck indefinitely as well as watch his entire crew die around him.

Voight explores the same theme of human struggle and its manifestations. His works, which combine photography, painting, drawing, performance, digital collage and photo manipulation, all coalesce, as he demonstrated to viewers at Fisher Gallery, as a means of coming to terms with our burdens and the beauty that can be found in pain. As he explained it: “Through my work I seek to create a visual journey through confronting tribulations present within our lives — by attempting to shed the anchors that weigh us down and fight the demons that haunt us, we can achieve measures of transcendence and even tranquility within the chaos.”

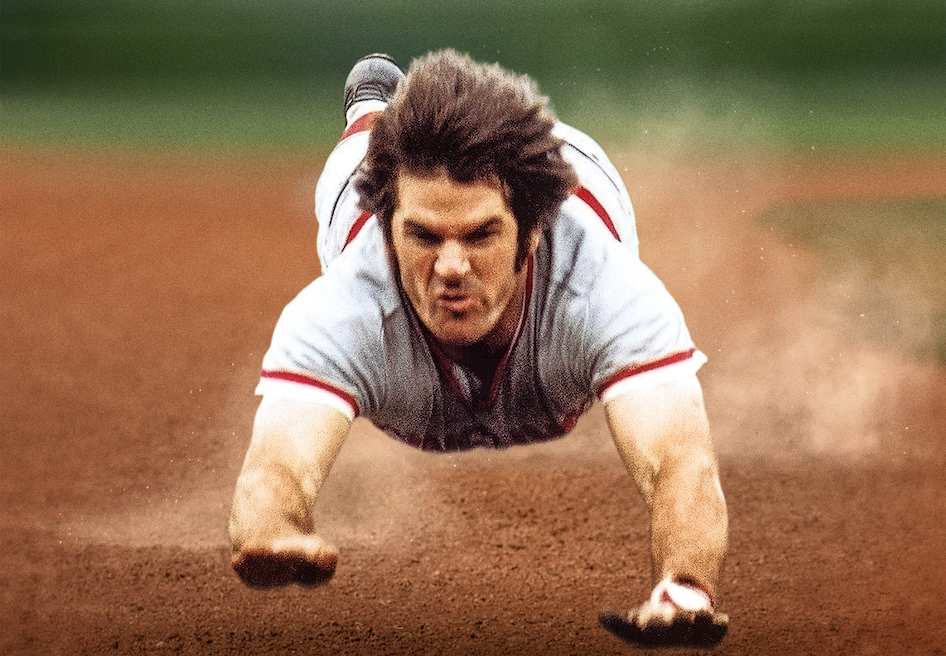

Albatross showed great continuity in its balance between struggle and emotional release. Voight executed expressive splashing of bright colors and the tension in his work is seen throughout. Particularly outstanding were the pieces in which Voight appeared as the, as they in particular illustrated a type of journey one must go though. He engaged with a performative technique, posing in various roles with his face and body painted, blending in with the supernatural background. You could see the pain on the gaping faces, further accented by morbid imagery of skeletons and zombie–like creatures, yet the beauty was unmistakable and euphoric. While still remaining dark, the ecstatic quality was achieved through skillful digital editing and accentuated by the graffiti-esque, street–art aesthetic present within all the pictures. Voight’s show was a beautiful, tactile diamond in the rough. It was raw and ventured far beyond the ancient mariner’s ship.

Kron’s show, titled Man or Animal, involved a similar theme to Voight’s, responding to Gilles Deleuze’s essay, “The Body, the Meat and the Spirit: Becoming Animal.” Evoking a similarly raw aesthetic, Kron explained that Man or Animal was a comment on man as an idea or the psyche as well as abstracting the human form to just legs, or a set of abs, the face or just a few features.

By abstracting various body parts, Kron’s work functioned like a study of the human body and sought to demonstrate how one limb, for example, can operate as a proxy for the entire human form — a kind of visual synecdoche.

Though her resin organs stole the show with their beautiful delicacy, Kron’s sculptures particularly stood out with for their grotesque, unpolished surfaces. Her plaster leg installation, titled “Pygmalion,” most aggressively demonstrated her show’s theme. Kron erected a series of life–size plaster legs intended to evoke the sensation of the “half realized” which, as she explained, “is why each foot was emerging out of an unfinished muscular form.” The rough surfaces of Kron’s sculptures, which make visible the evidence of the artists touch, reinforced her interest in the corporeal in their inclusion of the artist’s (human) presence. We were able to see the humanness and raw body form.

Lining Fisher’s east wall were a series of busts whose forms metamorphosed from the primitive to the more sophisticated as they moved from right to left. The intention behind this work was to reference Greek mythological in the warning that when people spend less energy worshiping their gods they begin to disappear. More intriguing however was the progression that the faces go though. Each bust began to degrade and the facial features lessened down the line, like a type of birth, or evolution from animal into man.