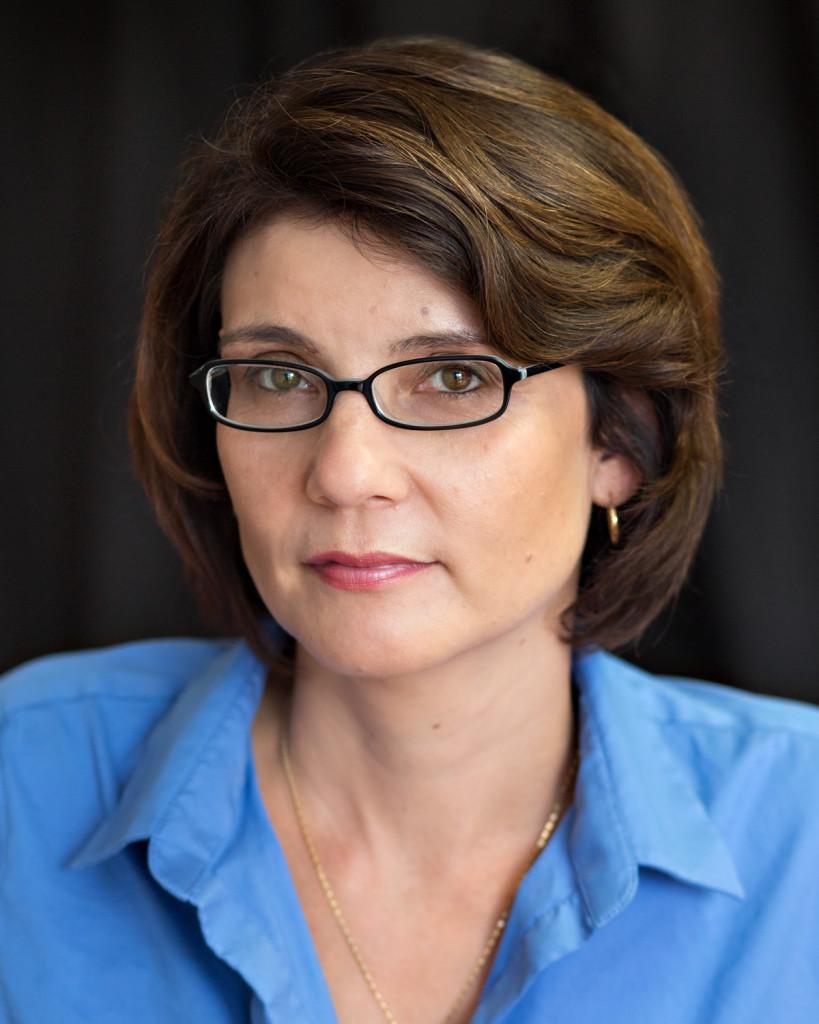

Off the Cuff with Sheila Miyoshi Jager, director of East Asian Studies and author of *Brothers at War*

Sheila Miyoshi Jager, an Oberlin professor who recently published her third book about the Korean War’s modern impact

November 15, 2013

Sheila Miyoshi Jager, associate professor and program director of East Asian Studies, recently published a book that illuminates the military, political and cultural history of the Korean War. She sat down with the Review to discuss the East Asian Studies department, the publishing process and the Korean War.

Can you tell me a little bit about your recently published book, Brothers at War?

It’s a book about the Korean War, but it looks at not just the operational history of the war, but it also looks at the relationship between the military and society, and it looks also at memories of war. And it of course takes the broad perspective, not just the Americans, but of course Korea, China and the Soviet Union, so it’s about sort of a regional complex. But I think what distinguishes the book is that it’s not just looking at the war years which is 1950–53 or even earlier, 1945–53, but it takes a look past the armistice, past 1953, to look at the impact of the war on East Asia, because the war never ended. The war ended in an armistice but never a peace treaty so in effect we were still at war. We were still at war basically with North Korea.

And how far does the chronology go?

Basically to the present. It actually ends in December 2012 which is when I had to give the book up. But the paperback version, I’ll probably even update it a little bit more, because the book ends with Kim Jong-Il’s death and of course there’s a new leader in North Korea today, Kim Jong-Un. And a lot of people thought that he was going to be this new reformer. He’d been educated in Switzerland, and [they thought] that there would be a new era for North Korea, but it looks like he’s a pretty hard-liner. And reform is not really on the horizon for North Korea.

So what inspired you? How is this subject different from others you have explored in your previous two books?

My focus has always been South Korea. My interest in the war [came through] memories of the Korean War because I saw that South Korean memories have changed dramatically. From the early 1960s when it was really during the Cold War period, North Korea was viewed as this terrible enemy, sort of this devil. And then during the 1980s, views of North Korea sort of changed. There was this big incident called the Gwangju Uprising and that included the South Korean government forcefully suppress[ing] this civil uprising, [killing] many people. And at that time, many student dissidents began to question their government and also question their government’s relationship to the United States. And so they began to look at North Korea as maybe an alternative to their own government, among dissidents and intellectuals. And then of course during the 1990s, the Cold War ends and North Korea basically collapses. And so there’s this new movement to look at unification and this sort of way of “We can reconcile with the North and help the North” but it was really more of an absorption of North Korea than anything else. So there are all these sort of changes in the way in which South Koreans have looked toward North Korea and looked toward the Korean War and I was interested in those changes. So I got this position at the U.S. Army War College and it was basically a policy position and they told me, “I want you to look at the Korea situation.” So I thought, well, I needed to understand the relationship between North and South Korea from the very beginning if I’m going to understand really how South Korea became South Korea and North Korea became North Korea.

Now in the process of publishing this text you had to promote it and contend with the opinions of reviewers. What was that like?

It’s interesting because I published the book in July, which was supposed to be the 60th anniversary of the armistice, and I published it with Norton which is a commercial press, and it’s different from academic. And of course, I had a publicity person assigned to me and she did a lot of trying to get me [promotional] stuff. And of course I got National Book Fest which was sort of a big hoo. But I think the book really took off when the Economist did a review and that was two or three months later; it was like this dark period. And they took it and they did a favorable review and after that, I just started getting all these [reviews] — the Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, Foreign Affairs. I mean the industry’s sort of building and building. So I really feel like it was the Economist review that sort of pushed it and everything else took else after that. It’s very different because you have to promote the book. And because it’s a commercial press, I’m sort of obligated to do these things. [Laughs.] I didn’t really want to do this stuff, but I mean I was sort of obligated to do it.

Recently, there was a New York Times article about your book. And then, of course, President Krislov wrote his Letter to the Editor about the humanities and Krislov almost came to their defense and I was wondering if you had any opinions about that?

Well it’s interesting because I studied the Cold War and George Kennan who was the founder and author of containment policy. He made an interesting remark when he said, ‘When I formulated this strategy about containment, I wasn’t looking at political science or I wasn’t looking at economies of the Soviet Union.’ He was understanding the Russians and Russian mindset through literature. And I think that it’s really important to understand another society, to formulate your grand strategy and policy, you have to understand who you’re dealing with. And how do you understand a person’s culture and history if not through literature? And so I think literature and humanities and history all are extremely important because those are the vehicles through which we understand the world and it’s not just for our own pleasure but really for very important policy issues. So it has practical import, and I think Kennan is a really good example of somebody who completely really understood Russia through Russian culture. And we train foreign service officers, we train military officers, we train anybody who’s working in the government, anything practical, we really need those kinds of people. And so that to me is a good advocacy for why the humanities are really important.

As we enter the registration process, what courses are you looking forward to teaching next year?

I’m teaching a seminar course called The Opening of Korea. It looks at the Korean War. The Korean peninsula even at the end of the 19th century was an object of superpower rivalry and at this period in history, it was a very important period because it was the change between a Sinocentric — a China-centric — world order in East Asia to a Japan-centric world order in East Asia. So I’m looking at that huge transformation that happens from China- to Japan-centric and how Korea plays this central role in that transformation.