Oberlin Alum Explores Family, Food, Humanity in Memoir

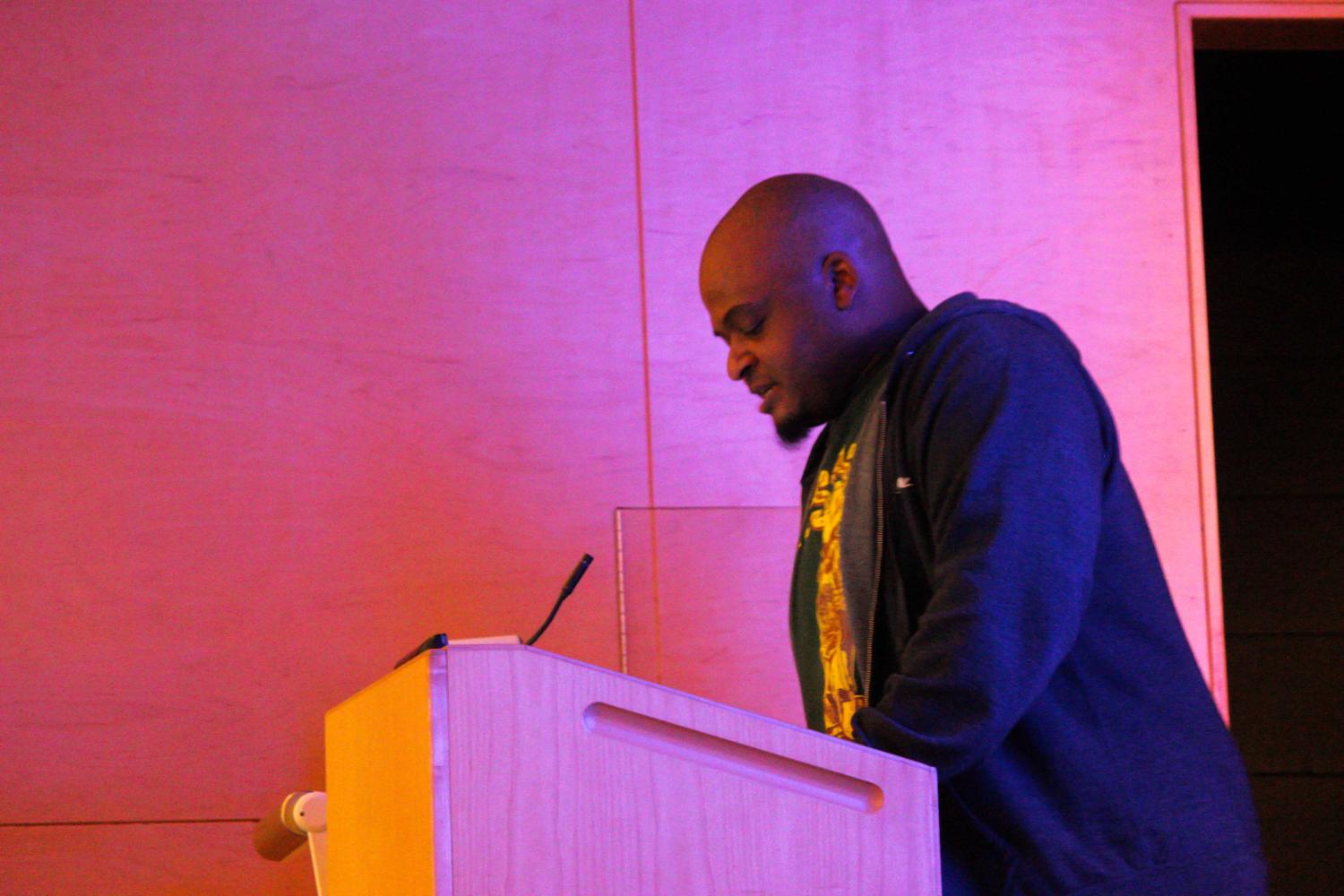

Author Kiese Laymon, OC ’98, returned to Oberlin Monday afternoon to give a reading from his new book Heavy: An American Memoir.

September 15, 2017

In his new book Heavy: An American Memoir, Professor of English and African American Studies at the University of Mississippi, Kiese Laymon, OC ’98, discusses his “family’s relationship to food, sexual violence, and weight.” Heavy explores Laymon’s interpretation of the lessons he learned as a child from his mother and grandmother, and the role of language as a powerful protective force for Black folks in white spaces.

Last Monday, Oberlin was fortunate enough to host Professor Laymon for a reading of his new book. The reading began with an introduction by Associate Professor of Africana Studies and Theater Justin Emeka, OC ’95, who described the stakes of Laymon’s work.

“Kiese’s thoughts are always challenging us to be prepared to rethink how we understand humanity,” he said. “Because how humanity was defined fifty years ago is different than a hundred years ago, and different than a hundred and fifty years ago, now, in our time, we have an enormous responsibility. All of us who come to this institution are actively engaged in trying to construct our own humanity as well as the humanity of the entire nation.”

The construction of humanity was a theme of the night. Oberlin students who include the intersections of race and gender in most of their writings and conversations may shy away from sharing their thoughts in a predominantly white institution like Oberlin for fear that they will not be accepted, or could be considered “too political.” Charmaine Chua, a graduate of Vassar College and a former student of Laymon’s, and currently Assistant Professor of Politics at Oberlin, organized the reading and spoke about how Laymon reminds her of her mission to teach her students the importance of personal and vulnerable perspectives on political topics.

“While you talk about massive things like terrorism, 9/11, all of these things that people want to write about in a distanced way, [if ] you write about it in a way that dares to talk about who you are and how you saw that from where you were, it shifts the view. I think it’s crucial that we never think of ourselves as somehow removed from the political things that we’re involved in. As a politics professor … part of my desire as a teacher is to remind my students of that.”

She also spoke about how the reading helped her meet multiple professors from various departments.

“What’s really cool, especially at a place like Oberlin, is you can talk to Creative Writing and Africana Studies and Theater [people] and everyone wants to hear what Laymon has to say. Everyone knows that there is a way that art, personal narrative and storytelling intersect. … I’m new here, but I’m excited to be a part of that community.”

Kiese Laymon reminds readers of this idea of community in Heavy: An American Memoir. He embraces the language and vernacular he used as a child growing up in Jackson, Mississippi to craft his own language. To paraphrase, he created a tradition where there was none before, and this is what he challenges young Black readers and writers to do. Laymon also wrote Long Division, a novel that takes place in post-Katrina Mississippi, and How to Slowly Kill Yourself and Others in America, a collection of essays. In his works, he illustrates the level of intimacy and self-exploration that the totality of the Oberlin community of all identities can achieve through language. Particularly for Black people, language is a tool of survival. Language helps people feel a part of a community larger than themselves, and being a member of a community committed to the success of its individuals is power in and of itself.

According to Professor Emeka, where we are now is just the beginning.

“I think it was really important for students to hear his voice partially to help them realize the potential of their own voice,” he said. “You never realize how powerful your own voice is, as well as [that of] your classmates around you. You all are going to write books and make companies and be heads of state. You can’t really see it right now, and you don’t need to. But you need to be aware of the fact that the deep relationships you are making today are deeper than what you see.”

Much like the many students that are growing and developing at Oberlin today, Laymon says that he was nurtured here.

“It feels wonderful to be back at Oberlin,” he said. “In a lot of ways, I mean, honestly, Oberlin helped make me the writer I am today. It gave me my first real, vibrant Black arts community and I think I grew in the three years I went here much more than I would’ve grown anywhere else.”

Laymon’s reading conveys the message that humans must continue learning and growing in ways that will strengthen our voices. It is a long, slow, and difficult process, but through it we can learn to be our true selves, and therefore be truly human.

Speaking on Laymon’s presence as an Oberlin graduate, Professor Emeka said: “For him to come back and say ‘I was you’ also implies that you are him.”